Tom Kenny – Contextual Light

Posted on September 9, 2021

Where does one go after working for U2 at age 14? For this Irish-born, and now Florida-based, designer, the answer is onto a storied career that as seen him light shows by stars like The Who, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, Taylor Swift and Elton John, along with an array of major awards ceremonies, TV programs, and films.

Rising to a preeminent position in his profession, Kenny has worked with massive rigs involving thousands of fixtures at giant arenas and stadiums. Through it all, however, his focus remains virtually the same as it was decades ago when he lit local bands in small Irish pubs.

Strip away all the DMX universes, powerful movers, elaborate set pieces and sophisticated automations and his designs are driven now as they were then by the artist on stage. Just as even the mightiest wave draws its very existence from the sea, every lighting design, from the grandest to the most modest, lives only within the context of the show or event that spawned its creation.

Strip away all the DMX universes, powerful movers, elaborate set pieces and sophisticated automations and his designs are driven now as they were then by the artist on stage. Just as even the mightiest wave draws its very existence from the sea, every lighting design, from the grandest to the most modest, lives only within the context of the show or event that spawned its creation.

Adhering to this philosophy, Kenny has created a long list of innovative designs that accentuate the most important elements of his client’s shows without distracting from the performance on stage. This very-much-in-demand designer took a break from his busy schedule to talk to us about the power of contextual light.

You once said that although younger designers “may think that they have it made when they have a huge system, that’s not necessarily the case.” What did you mean?

“Experience working with big rigs teaches you that it’s never about the size of the system, it’s what happens on the stage in its entirety that really counts. Sometimes even in a huge show with hundreds and hundreds of fixtures, the most memorable moments are those subtle ones that convey a sense of intimacy. That’s often what people take home with them. Regardless though, in all circumstances a show, however big, should never overwhelm the talent on stage.”

Of course, you’ve famously worked with some massive systems. So, what is the key to managing large rigs so they don’t overwhelm?

“It comes down to how you decide to use your fixtures and whether or not your design is dictated by the content of the show rather than just doing what you want because it looks good.

“You also got to have a good programmer and a good gaffer. Our Vax Live project was a prefect example of that. Our loaded in was done in a couple of days and we had the rigs flown in 10 hours. All of this in a venue (SoFi Stadium) that had never been rigged before. When you have talented people like that working together even the most massive rig becomes more manageable.”

Is there a Tom Kenny look?

“Yes.”

How would you describe it?

“It’s big and in your face in a way, I suppose – but definitely not flash and trash. If you look, I probably have fewer cues that most people. Every beat does not have to be accented by light. The music can do fine on its own sometimes, unless your client is not that good of a rock star! As we just talked about, it’s not about being massive for its own sake – everything has to fit in the context of supporting the people on stage.”

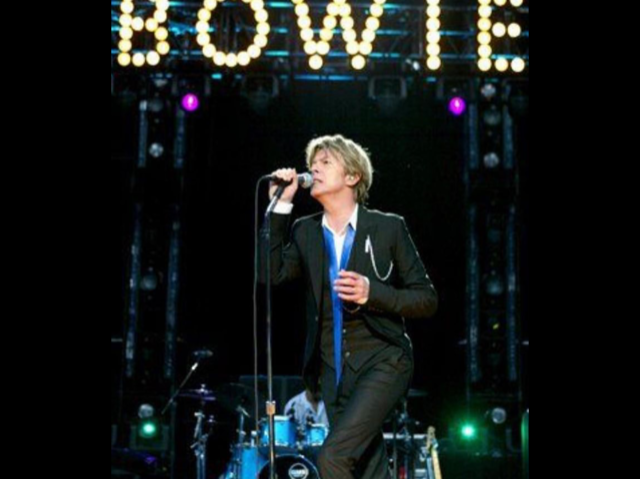

Speaking of the people on stage, you’ve designed for a great many stars including legends like David Bowie, Robert Plant, The Who and Eric Clapton who’ve already become icons. Given their legendary status, do you try to reflect something of their tradition and history when you design for them?

“When you light artists who’ve had these legendary careers, you have to respect who they are and what they’ve done. It’s important to keep them center stage, so follow spots and key lights are especially important.

“However, they also want to add new elements to their stage presence every tour. They’re the types who are always curious and ready to explore. That’s one of the reasons they became mega stars. So, I will not hesitate to add new things. I once did some unique specials for Eric Clapton to light him during one of his long blues breaks. He loved it, which of course made me feel good. It’s always means great deal when they trust you.”

So, is there a great artist from the past, who you wish were still around today so you could light a show?

“I would have loved to have lit Sinatra. Once, I came close to doing that, but it didn’t happen. His class and style would have been fun to light though. A couple of years ago, I lit Tony Bennet, which was probably close to what it would have been like with Sinatra. The other one who would have been cool to light is Janis Joplin.”

You’ve worked in a very wide range of genres for a great variety of artists. Do you have to like someone’s music to do a good job lighting it?

“No, not really. It’s funny, I listen to a client’s music relentlessly, even if it’s not my taste. If it’s good music, even if it’s not your taste, it’s easier to come up with ideas. If it’s not good music, you need more cues.”

Does the personality of the artists influence your design decisions?

“Yes, a great deal sometimes. You’d be surprised, but a lot of stars are not bold on stage. Sometimes they’re nervous about their performance. So your lighting has to take this into account and perhaps cover for them or encourage them.”

Given the size of many of your shows, do you ever busk?

“Oh yeah, all my life! It’s not like I’m the LD for a jam band, or anything like that, but I very much enjoy busking and do it in many projects, like at the Vax Live event, what Mark and Dan did when the Foo Fighters just broke into improvising. To me, busking is like playing an instrument. Of course, I don’t get out on the road to busk on tours like I once did – it’s a young persons game. Fortunately, I have some good young programmers, women and men, who do a great job running the shows I design.”

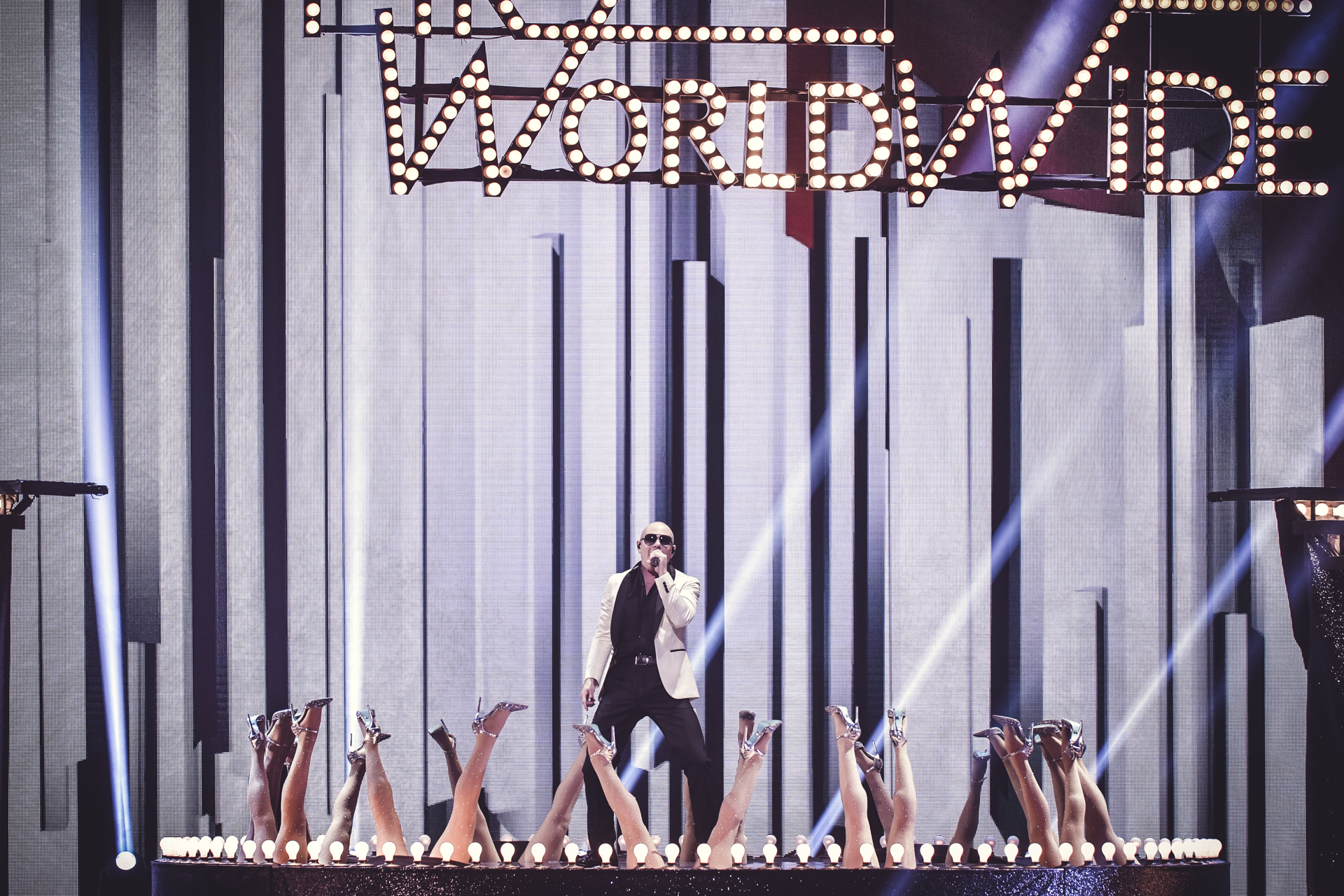

In many of your projects like Premio Lo Nuestro, the Univision Awards and The MTV Awards you create a concert look as well as a glamour award show vibe, all while fitting the parameters of a broadcast application. When you have to balance three different demands like that, is there one that you start with?

“I start with the faces. If you don’t get that right, nothing else is going to matter. Regardless of what you have going on 75-percent of these types of shows are going to consist of closeups. Next I go to the music, since the show has to feel like a concert when artists are performing. Then, I will tweak production for walk-ons and presentations.”

You had 21 different acts performing on stage in that Premio Lo Nuestro we just mentioned. Even with a big rig, there are only a finite number of fixtures to work with. So, how do you ensure that you’re able to create unique looks for each act?

“The variety comes from the artists themselves. You get into their music and stage personalities and blend your lights to fit this content. This not only gives you the variety, it also results in a more compelling show. One of my best looks was for an appearance by Rhianna on an award show. Studying what she would be preforming, I created a look where the stage went from red to blue. It was one of those magical moments where everything came together – and it came about as a result of immersing my creative process in her content.”

Many of your designs have massive video walls, yet your lighting never seems to be overwhelmed by them or get in the way of them. How do you balance video and light?

“Video screens suck the living daylights out of the live vibe. That’s really it in a nutshell. A video screen is one big light fixture, so it takes something out of the lighting. A set is more organic without the big video screen, but you often need video, so you work within that parameter and use your lighting to create a design that’s as organic as possible.”

You grew up and began your career in Ireland. How did that influence your development as a designer?

“I grew up with a strong musical tradition. My family were all musicians. So, I was surrounded by Irish music, which is rich in emotions and drama. I should think this is reflected in my approach to what I do today.”

How did you get started in lighting?

“As a young kid, I used to hang around the shows my older brothers were playing. Being too impatient – or may not talented enough – I never learned to play an instrument. Soon people asked me to help out by running the lights. So that’s how it stared. When I was running lights at the club one evening, this fellow by the name of John Kennedy asked me if I’d like to help out on a few summer gigs by this new band called U2. I was 14 years old at the time. A few years later I was lighting a fashion show that my dad saw. He came up to me after and said ‘you know, I think you can make a living at this.’ That’s when I was sure this would work out.”

What’s the most important thing every lighting designer should remember?

“Listen to the music and listen to people who know the artist. They will help you navigate your way through the business of touring.”

Looking at your own career, what is your greatest strength as a designer?

“That I can turn on a dime when necessary.”

How about your greatest weakness?

“That I can’t stand idiots –no patience!”

How would you like to be remembered as a lighting designer?

“I’d like to be remembered for all the innovative stuff I did. For how I made my clients look good – and for how I brought smiles to faces.”