Kenneth Posner – Enriched Light

Posted on July 5, 2022

On the surface at least, the brooding Baroque master Caravaggio appears to have nothing in common with the colorful, wafer-like Necco candies of the 1960s, but both have left their mark on the lighting designs of this Tony Award winning New Yorker. So too, at various times, have polka dot go-go boots, and the classic child’s game Lite-Brite Magic Screen.

Kenneth Posner has not come about this eclectic mix of influences by accident. A self-described “storyteller,” he recognizes, as all who practice the craft well do, that the most compelling narratives spring not just from the imagination and skill of the author (or lighting designer!), but from all the outside forces that inform the creative process, making it richer, fuller, and more meaningful in the context of its time and place.

Kenneth Posner has not come about this eclectic mix of influences by accident. A self-described “storyteller,” he recognizes, as all who practice the craft well do, that the most compelling narratives spring not just from the imagination and skill of the author (or lighting designer!), but from all the outside forces that inform the creative process, making it richer, fuller, and more meaningful in the context of its time and place.

Throughout his distinguished career, Posner has made it his mission to learn all he can about the worlds that the shows he lights inhabit. At times this has meant studying the light angles and shadows in a 17th century Italian painting; at others it’s entailed dissecting a post-modern wallpaper pattern, or grabbing just the right palettes off a popular candy.

Posner has delved into this wide range of sources, to add layers of authenticity to his designs. The better, he believes, to reflect the story being told on stage. This practice has served him well. In addition to the Tony won for his work on Tom Stoppard’s “The Coast of Utopia (Part 2),” his portfolio includes significant shows such as “Kinky Boots,” “Cinderella,” and the revival of “Pippin,” all presented in the same Broadway season and all nominated for a Tony Award, as well as the current Broadway comedy “Mr. Saturday Night” with Billy Crystal..

In this interview, Posner shared his insights into the enriching effect of adding context to design.

Among your celebrated works are, “Wicked” and “Hairspray.” They come from very different ends of the reality spectrum, the first being based on fantastical Wizard of Oz characters, and the latter centered on a realistic character, involved in the very real struggle for racial integration. Did this influence your approach to lighting each of those shows?

“First and foremost, I’m a storyteller, and both of these shows tell great stories. In a very real sense both of those stories revolve around the same, important theme: inclusion. This theme is what makes them special and gives them power. But in these cases, the same theme plays out in different times and places. So in this respect, I followed the same narrative, but within somewhat different scenic settings.

“As you mention, ‘Wicked’ is based on a fantastical setting that’s large and spectacular. Eugene Lee’s scenic design, which emulated the inner workings of a clock, and Susan Hilferty’s magnificent costumes, created the sort of atmosphere that gives you license to be a bit more lavish with lighting.

“’Hairspray,’ on the other hand, is grounded in the world of John Waters’ Baltimore in the 1960s. So, in that case telling the story with light involved reflecting a very specific and very real time with patterns and colors at different locations. An interesting thing about ‘Hairspray’ is that we had a full-stage lit backdrop with 600 points of light. This was in 2002, so it was one of the first uses of LED in theatre. It was based on the classic Lite-Brite Magic Screen toy.

“The LED lights that made up our background were originally manufactured for signs, but we converted them for theatre use. We didn’t even have processing power to run this type of thing, so we had to use three different consoles, one for the Lite-Brite wall backdrop, one for moving lights, and one for conventional lights. Of course, today one console could handle all of this without breaking a sweat.”

What kinds of colors did you create on that backdrop?

“We let the narrative dictate that. Again, since this play was set in the ‘60s we used colors of that go-go era. Our scenic designer, David Rockwell came up with the idea of using Necco candies — don’t know if you remember them, but they’re still around today — for the color scheme, because they have this pale but vibrant palette. I enthusiastically embraced the idea. They worked wonderfully to convey the sense of time and place.”

So a familiar candy, and child’s game of the era inspired part of your color scheme and backdrop for this landmark show?

“Yes, absolutely. I always look to outside sources to inform my designs. This may involve studying wallpaper patterns, old advertisements, film, or whatever. We’ve even used the polka dot go-go boot patterns in that particular show. In my view a designer should always be looking at outside sources to help drive a narrative.”

Should a lighting design be a parttime historian too then?

“I think so. History was always one of my favorite subjects in school. I love it. In a way it was a chance to escape from this world and enter another, which always appealed to me. But beyond that, you really need to understand the context of a show’s time, place and people when designing. It comes back to being a storyteller with light. The narrative has to drive your design. And to understand the narrative fully you have to understand its context by informing yourself about these things.”

Your newest project, is the currently running “Mr. Saturday Night” with Billy Crystal on Broadway. How is lighting comedy different? Can you convey a sense of humor with lighting?

“You can convey humor, but again it’s story driven, not just humor for the sake of humor. ‘Mr. Saturday Night,’ spans different eras form the 1950’s Borsch Belt comedy circuit in the Catskills and the television comedy hour, to the 1990s, when the Billy Crystal character is looking back and reflecting on his career. I wanted the lighting to feel timeless in a way, so it could support the speed at which the story unfolds from era to era and contrast the time periods. This show also has great songs, which gives you permission to create more fantasy looks with your lighting. When you look at it, comedy is made up of words, but it’s also all about expression. Billy Crystal is a master at both, so I wanted to support that aspect of his play with the lighting.”

Do you use color differently for a comedy?

“Not consciously. Since my work is all narrative driven, I do what’s best for the interaction between the characters, the architecture of the scenery, and things of that nature. This is more my focus than conveying humor with color. But looking at the final result, you can see that I used warmer colors for ‘Mr. Saturday Night.’ It’s not like I said to myself use these colors because they convey humor, it was more a matter of following what the story dictated.”

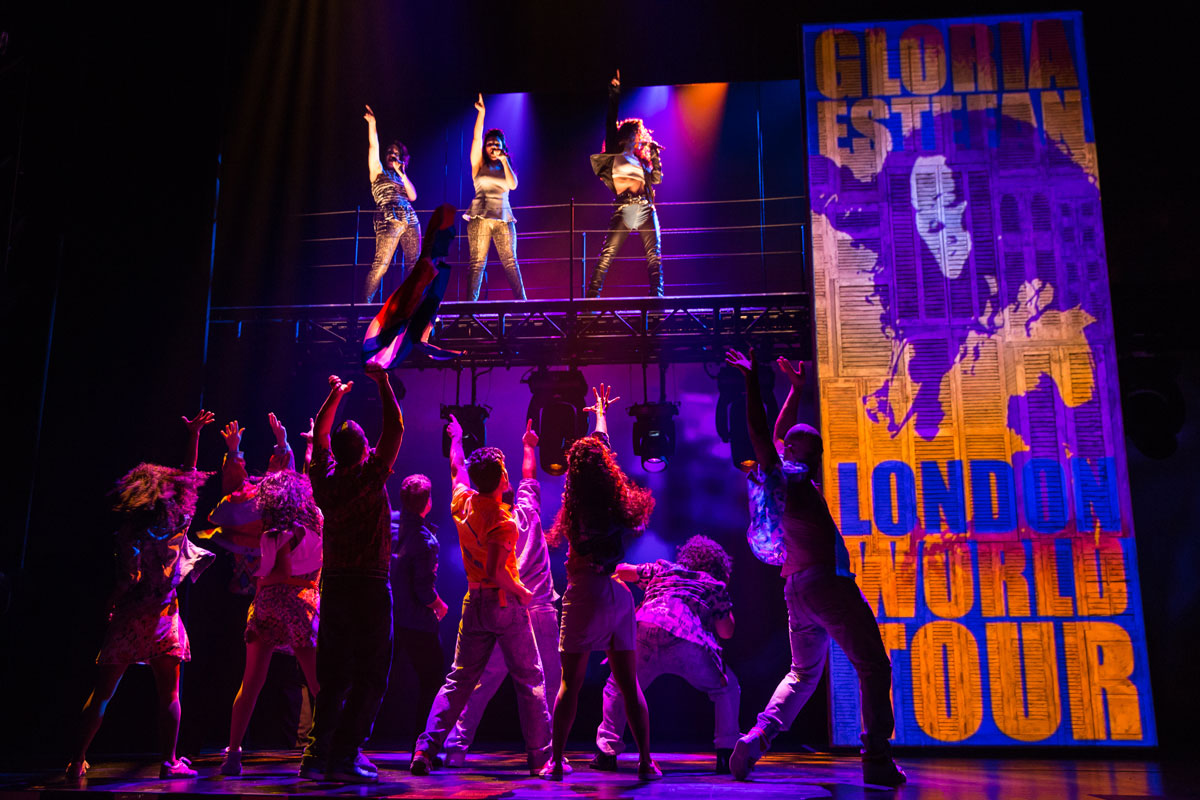

In some of your work, such as for “On Your Feet,” you make excellent use of moving fixtures in disco or dance club scenes. Has the role of moving fixtures in theatre evolved in recent years How do you use them and not over-use them on stage?

“Moving fixtures are another tool in your toolbox. When I first entered this business, movers were just starting to make their presence felt. There was resistance to them, particularly since they drove up rental prices, and because of the noise they made. The first objection disappeared when it became clear what movers could add to a show; the second when manufacturers made quieter fixtures. ‘Mr. Saturday Night” is 90-percent moving fixtures, whereas ‘Hairspray’ had only a few to augment the conventional light plot.”

LED video walls and projection videos have also become more prevalent in design. How do you integrate them into your work? Has the emergence of video pieces changed the way you use more traditional scenic elements?

“Again, it’s another tool in the tool box. I am not a video designer, so I don’t get involved directly in it, but I very much enjoy collaboration. The decision to use them is driven by the scenic designer or director. It changes how you use lights, since it becomes the biggest lighting source on stage. However, given the level of collaboration that exists between me and my video design colleagues, light and video invariable work well together.”

You have also made effective use of light angles to set scenes or change moods on stage? What advice would you offer on using different light angles?

“Glad you asked! In terms of how important light angles are, I can tell you that I start the design process with them. To me this is the most important element in storytelling. Light travels in a line until it hits something, then it reveals. This revelation is at the heart of your narrative – and how it happens depends on the light angle. So, it’s critical that your light angles be compatible with the scenery and the story being told.

“Light angles have to be driven by the narrative. The continuity of a design falls apart if the light angles aren’t compatible with the narrative. A couple of generalized examples: if the light angle isn’t highlighting the expression of a character involved in something important, much of the meaning of that moment is lost. On the other hand, if the light angle is revealing too much of a character in a suspenseful scene, much of the impact and mystery are lost. These are two extremes, there are also many, many more subtle ways that light angle shapes the story.

“To get a real appreciation of light angles, you should look at the paintings of Caravaggio. They totally transform his work. His light angles have such power, especially as they work with his shadows. I have studied them, as well as the works of other artists, to inform my use of light angles in my designs for shows.”

You mention Caravaggio. Are there historic painters like him who you think would make good lighting designers today?

“Henry Osswana Tanner, Edward Hopper… but all painters are already lighting designers when it comes down to it.”

Before you start working on a new show, how do you prepare yourself?

“I read the script one time just for enjoyment. Then I go back a read the script a second and third time to look for nuances and the relationships characters have with one another and the story in general. I’ll also research images and ideas involved in the play; and then I’ll discuss my ideas with the director and other designers.”

You won a Tony Award for “Coast of Utopia Part 2.” What stands out for you when you look back on that project?

“The collaboration with some wonderful and wonderfully talented people, including director Jack O’Brien, Natasha Katz, and Brian MacDevitt, along with the entire creative team, crew and the cast. That stands out more than anything.”

You’ve done so many significant shows. Are there any plays you never did that you’d like to do?

“Interesting question — I guess I would say ‘The Threepenny Opera,’ ‘Sweeny Todd,’ and I never did ‘Hamlet.’ Also, I’d really like to do ‘Caucasian Chalk Circle’ again. I lit it once for summer stock, but it would be really wonderful to do it on a grand scale at a venue like The Armory.”

When did you first realize you wanted to be a lighting designer?

“I always wanted to be involved in theatre in some capacity. What drew me to lighting design ultimately was when I saw ‘Chorus Line’ and Tharon Musser’s work. I saw the show three or four times. It was then that I fully appreciated what lighting could do and knew this was for me.”

What do you think you would have done if you didn’t become a lighting designer?

“That’s a scary question! If I did anything else, it would just be a job. The way I look at it now, I never had a job, because I’ve been in lighting.”

You’ve lit shows that starred a wide range of actors, do they ever give you feedback on lighting or make requests on how they prefer to be lit?

“Yes that has happened, and I embrace it. To me it’s quite an honor when an actor engages you.”

If you had one bit of advice to give an aspiring lighting designer, what would it be?

“See everything, — entertainment, nature, the society you live. Immerse yourself in the world you want to create, and learn all you can about it.”

Do you have a favorite play that you’ve worked on?

“Not really– in a way it’s like asking a parent who’s your favorite child? I love them all! But there are shows that stand out in my memory, not always because of their artistic merit or commercial success. Sometimes it’s because of the experience of working with the people involved.”

How would you like to be remembered as a lighting designer?

“As a designer who gave back to the community; who was supportive of the next generation; and appreciative of his peers.”