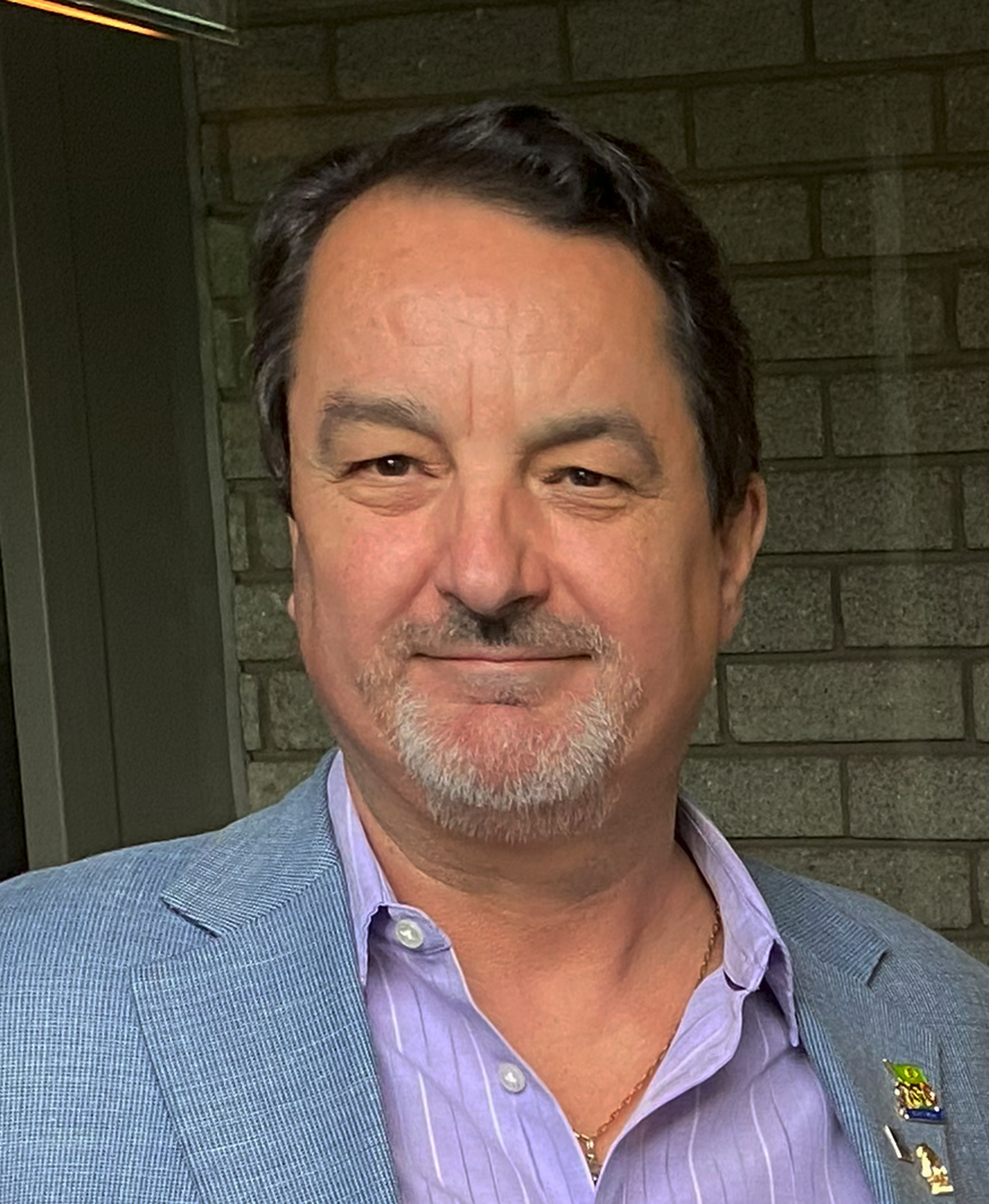

Durham Marenghi – Global Light

Posted on December 3, 2024

His first exposure to theater was on the stage, when his mother, an amateur dramatics director, prevailed upon him to don green tights and a swimming pool cap adorned with plastic leaves to play the role of Oberon King of the Fairies. As he stood there on the set, the young Durham Marenghi looked around and spotted the lighting crew inside their stage side “cage.” It didn’t take him long to figure out that this was where he belonged, and thus began one of the most highly acclaimed and awarded careers in lighting design.

In the ensuing years, the London-based designer has worked his creative magic at every manner of major, global project, including the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio and the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, The Queen’s Golden and Diamond Jubilee Concert at Buckingham Palace, the 100th anniversary of the Taj Hotel in Mumbai, the British Day Concert with Sir Andrew Lloyd Weber at the Seville Expo, The London New Year’s Eve Ceremony, the Qatar FIFA World Cup, The Wall concert with Roger Waters in Berlin, and too many other spectacular productions around the world to list in a single article.

Although his works span virtually every genre of lighting from rock concerts, to museum installations, to shows and broadcast productions, theatrical lighting principles and sensibilities remain at the heart of Marenghi’s approach to design.

Although his works span virtually every genre of lighting from rock concerts, to museum installations, to shows and broadcast productions, theatrical lighting principles and sensibilities remain at the heart of Marenghi’s approach to design.

How could it be any other way? In theatre, where he cut his teeth, working at houses such as The Belgrade Theatre in Coventry, the Yvonne Arnaud Theatre in Guildford, Young Vic on the South Bank and the Adelphi Theatre in the West End, Marenghi learned the basic principles of supporting unfolding narratives in light, teaching him lessons that would serve him well in every endeavor.

Just as he has carried his theatrical roots with him throughout his career, Marenghi has also retained his youthful passion for aesthetic excellence, something he shares with his photographer-spouse Jennie. The wry humor from his early days also remains very-much intact. This was readily apparent to us when he shared nine lessons he’s “learned illuminating the work of others,” which include the observation that artists past a certain age expect “the LD to have the skills of a plastic surgeon.”

On a more serious note, Marenghi also discussed the rapidly evolving role of AI in design, the immersive qualities of projections, and other valuable insights, all gained through his experience channeling the global power of light.

You began your career in theatre and you’ve talked about bringing your sense of theatrical lighting to you designs for opening and closing Olympic Ceremonies. The size and scope of these ceremonies is quite different from actual theatrical productions. Can you elaborate on what you meant by bringing theatre to those designs. Also, how you translated your theatrical design concepts into these massive productions?

“Lighting in a stadium is very much like lighting in a theatre in the round — though admittedly, the Maracanã Stadium was a little bigger than the Young Vic Theatre where I was resident lighting designer in the late seventies. I try to use the same angles and techniques but multiply the amount of sources needed to achieve the requisite light levels, but from similar angles when possible.

“An example of this would be the ‘Tab Warmers’ for the Giant sipario curtain designed by Mark Fisher for the Winter Olympics in Turin in 2006. Before the curtain opened to reveal Pavarotti, it needed lighting so we had around twelve 4kw blinders in pop up footlight traps in the forestage and this created an effect that we would have used two Fresnel’s to create in the theatre, the lighting principal however is the same just magnified!”

Of course, the Olympic ceremonies are broadcast internationally on TV. How do you balance designing for the live event and television audiences?

“The producers of the Ceremonies along with the Olympic Committee make it clear that the event is primarily for the 3 billion TV viewers rather than the 70,000 in the stadium so we follow that decree. However, we do of course try and make the show look good for the live audience — and the most important attendees, the athletes.

“Since the inclusion of field of play projections first used by Bob Dickinson in Vancouver in 2010 — remember the whales and the smoke spouts set into the pitch — we have an issue that is a challenge to resolve. The light levels in a stadium for football matches for example are around 2,000 lux whereas the light levels we can use without washing out projection tend to be no greater than 200 lux!

“This makes the live event very intimate and as the projected creative segments are interspersed with protocol moments, such as flag raising, cauldron lighting and the athlete’s parade, we need to keep the protocol sequences lit at similar levels so as to avoid massive aperture changes for the cameras. This often leads to comments from the OCC that the lighting is quite dark for their sections compared to what they might expect at a soccer match — and the lighting designer has to justify this. Really, 90-percent of the LDs work on these events is such politics once the design has been committed to paper.”

As we mentioned, you started in theatre and achieved success there, working on West End productions. Why did you branch out into other genres, rather than continuing to focus on theatre exclusively?

“After working at The Belgrade Theatre in Coventry and the Yvonne Arnaud Theatre in Guildford I was appointed Chief LX/Resident LD at the Young Vic on the South Bank. I then moved to the Adelphi Theatre in the West End as Deputy Chief LX under Tommy Thomas. From there I lit various tours and West End shows but an important new factor occurred when a company called Imagination moved into an office in Maiden Lane opposite our stage door.

“Imagination’s lighting designer wanted to hang some snow effects from our building to create the first of Imagination’s renowned Christmas facade displays. The LD was Andy Bridge who I had met in Guildford where they tested many shows before transferring to the West End. We formed a lasting friendship, and I worked with Andy not only in the West End as a rigger and production electrician but also on the Mega car launches prevalent in the eighties. This gave me a taste for the Spectacular live event.”

You work on an impressively wide variety of projects – concerts, events, ceremonies, fashion shows, exhibits and more. Of all the “genres” you work in, which has the most unique set of demands or challenges? In other words, is there one genre, where the lessons you learned in other genres apply to a far lesser degree than they usually do?

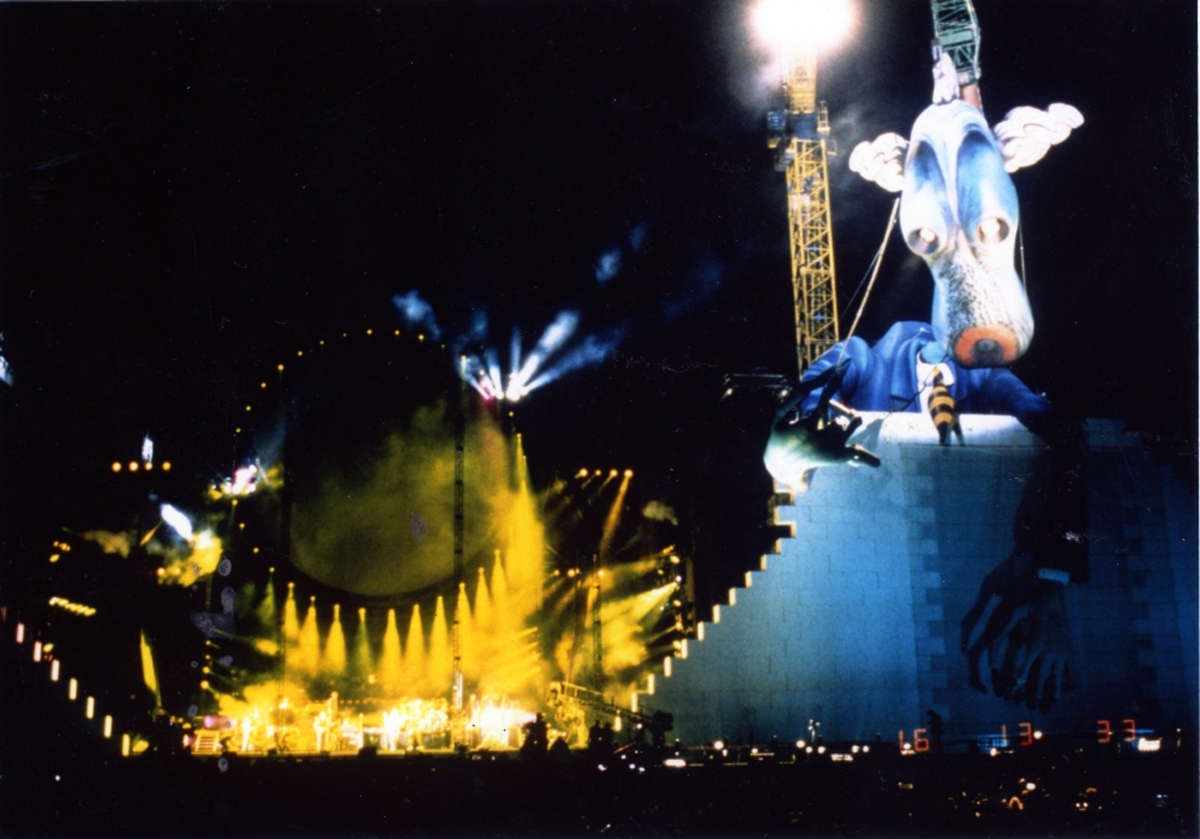

“I think the most unique experience and a real eye opener for me was ‘The Wall’ for Roger Waters in Berlin in 1990. I had worked with the creative designers Mark Fisher and Jonathan Park in the trade show world and had experience of music from my work in opera, West End and touring musicals, a UK tour with the Sex Pistols and Madness (with LD Simon Tutchener), and a few broadcast events from the West End and the RAH.

“I heard on the grape vine that the LD for the event lighting for the upcoming Wall concert, to work alongside the concert stage LD Abigail Rosen Holmes, had pulled out so I contacted Fisher Park expounding my resume. I subsequently found myself in no man’s land in Potsdamer Platz lighting without doubt my biggest event and arguably the largest live music event of that decade.

“I was responsible for lighting Mark Fisher’s 550 foot by 82 foot high ‘Wall’ along the forestage and lighting this with par cans from two construction cranes above. I was also tasked with lighting the massive Teacher and Pig inflatable puppets and I worked with Alan Thompson at Theatre Projects to develop the Sky-Art searchlights capable of spotlighting these huge objects. Trying to light them with conventional follow-spots would have looked out of context and lilliputian in my mind.

“I was also responsible for audience lighting and aerial search light effects and formed a great team of technicians with whom I have worked with over the past decades ever since. I firmly believe that any lighting design can only be as good as the technicians who realize it and they are the fundamental key to any success that we might enjoy. This was without a doubt my ‘big break.”

You were drawn to lighting design at a very young age. What is it about this profession that so attracted you?

“That is an easy one, my mother was an amateur dramatics director and at one point had her then fourteen year old son stood onstage in green tights and a swimming cap adorned with plastic leaves playing Oberon King of the Fairies much to the amusement of my friends.

“At the side of the stage I spotted two guys inside a metal cage drinking tins of what I assumed to be beer, and laughing uproariously along with my peers at my supposedly somber Shakespearean debut. That looked like a far more suitable way for me to skip classes, it turned out they were the lighting crew and the rest is history.”

If you didn’t become a lighting designer, what career do you think you would have pursued?

“As part of my Duke of Edinburgh Silver Award at school I worked with a local vet and was convinced that would be my vocation, I changed my A levels to science at the eleventh hour and could have studied veterinary science at university. Unfortunately, I become enthralled by the theatre, disco, and live music shows and the prospect of spending six years studying for a proper job, as my Mother would say, did not have the same appeal to my eighteen your old self!”

In many of your designs, particularly the Olympics, it seems that you like to cover space with projections, rather than washes and beams. Is that accurate. If so, why?

“Projection when appropriate can create a magical environment in which performers can tell our stories with far more clarity and impact than lighting alone can create. It does have its own challenges in terms of light levels — and I look forward to a time when LED floors will be able to be deployed over a field of play in a way that is economically viable, so we can get our lighting levels brighter for our live audience…and the OCC!

“It is important to realize that anything that produces light must be controlled or at least understood by the large event LD, fireworks, LED screens, stadium corporate boxes, vendor stands visible in the corridors and even the Olympic cauldron can significantly impact on our work. For months after the Rio Olympics the corporate guests at the Maracanã stadium must have wondered why the soccer matches seemed dark as we forgot to remove the tinted film to control light spill from their windows when we left.”

Something we always admired in your designs is your readiness to mix a variety of colors, often not primary ones, in a single tapestry. Some designers are afraid of mixing too many colors. Can you tell us a bit about you vision of color mixing?

“I can without a doubt attribute my understanding of color to Andy Bridge, I remember being really impressed by one of his theatre productions in terms of how we could use a four frame color changer to create around eight usable colors; I try to create by painting with light as any artist would and not limit my color palettes id possible.

“Having said that for multiple camera events I determine a more fixed palette of fewer colors for each segment, if we light these with too many hues then when one camera cuts to another the continuity is difficult to maintain. If we illuminate these events with too many disparate colors then the viewer might think he is seeing a different show from even perhaps a different venue as the editor cuts between shots!

Another thing that has always impressed us is that even in your major designs that are broadcast on TV, you manage to work dark spaces into your panorama. How would you describe the role of dark space in your design?

“By the Royal Opening of St Pancras high speed railway station—once the producers had decided to incorporate video sequences into the event, it became an environment where we had to be able to control ambient light. This meant turning off the brand new architectural lighting in the Barlow Shed and rigging above the electrified tracks, a story in itself.

“The real issue became apparent when we started negotiations As any theatre LD will tell you, you ideally start with a blank canvas and that is darkness. In these environments that can be a real challenge in itself. I argue that you would not ask a sound designer to work effectively in the din of a construction site or loud radios so why should we work in the ’din’ of working lights, grow lights, stadium lights or whatever else fate can throw at us.

An example of this issue can be illustrated with the other contractors to achieve darkness for our lighting sessions overnight. As they were working 24/7 to complete the building renovation, and were under very strict financial penalties to fail to do so, turning the lights out for some lighting bloke was not high on their agenda!”

You designed London NYE every year for an extended period. How did you keep that looking fresh year after year?

“I designed the lighting for the New Year’s Eve event at the London Eye from 2004 up until the pandemic and then designed the lighting for the two ‘secret’ city wide NYE shows during that terrible time of lockdown when we were tasked to create spectacular shows that must not attract any kind of live audience.

“At the Eye each year we carefully broke down the fireworks sequences into colour, timing and dynamics and reflected that as best we could whilst syncing the effects to the sound track with 25 fps accuracy. One of the main challenges was that the wheel had to remain open to the public for anything other than overnight rehearsals and the show itself. The lighting of these events is now in the capable hands of Tim Routledge.”

Looking beyond landmarks and architecture, do you try to reflect the “personality” of an event when you light it?

“Lighting designers exist fundamentally to technically support the artists, and any design has to accentuate their performance and make their personality and/or presence ‘larger than life,’ this applies to solo artists, mass choreography or even inanimate objects such as cars and trains. In this regard, a few things I have learned in illuminating the work of others include:

- Well-choreographed dance needs a lot less lighting changes than a crap one.

- Performers of a certain age expect the LD to have similar skills to a plastic surgeon.

- If something is truly awful it is expected ‘the lighting will fix it.’

- Mind your precedents… We employed you because we know you can work without those tedious and time consuming lighting sessions.

- If a performer states that he will stand in a specific place make sure you have a follow-spot or a good moving light programmer.

- The chief of mounted police amongst one thousand camels is the guy with the flashing blue fuzz light strapped to his head, obviously.

- If a cow is allowed to sniff a 1500w flood light it will stick to its nose.

- Opera sets always used to look best to a set designer when the working light was on as it reflected the Anglepoise over the model they designed to. Turn them off at your peril, or put them on a dimmer.

- When lighting historic events for TV it is up to you to make everything visible and up to the TV director to decide whether to show it or not.

“This last point refers to the Hong Kong Handover Ceremony in 1997 when Chris Patten was visibly upset and seemed in tears in the pouring rain when the band played Nimrod, I called my follow spots to fade to give him some privacy and was immediately reprimanded by the TV director. A subsequent National newspaper showed a picture of this intimate moment with the caption ‘Governor Chris Patten caught in the cruel spotlight of British lighting designer Durham Marenghi.’”

James Joyce was supposed to have said, “writing is never finished, it’s abandoned.” Do you find that to be true of lighting design? How you know when a design is complete? Do you ever feel there is more to do at the end of a project?

“To the contrary if you are given too much time both yourself and others will try and ‘improve’ the original creative work, always keep the first cues, so that you can re-instate them later. One of my particular issues is that if I create a design for a pitch that is then not released, I file it way as part of my design history, you can lose a lot of good work that way!”

Earlier, we mention projections. Given their growth along with the development with AI and VR tools, do you see the role of traditional lighting fixtures changing?

“I think that programming will change first. We are already seeing algorithms in desks creating effects sequences and in my mind that is really AI in its infancy. I recently proposed that we motion capture a Triad dragon dance and recreate that movement with lights and laser beams for a city wide show in China.

“Another fascinating development is parametric control whereby our recorded displays are affected in real time by external factors such as weather, movement of objects and people, calendar events and even the mood of a nation.”

You’ve done so many big projects, many of them might seeming daunting at first. So, how do you get inspired at the start of a project? What do you do to get the creative juices flowing?

“When I am approached to design such projects, we start with our aspirations and do not consider too closely how we might achieve them in the realities such as fixture placement, practicality and of course budget. The feeling that you experience when all these ambitious concepts are given the green light by the client is a heady mix of excitement and absolute terror.”

Do you ever procrastinate at the start of a project?

“I have learnt that whilst blue sky thinking has its place — I once investigated using reflective panels deployed by satellites in space, which it was rumored were being used to grow crops at night, to light a stadium event in Italy, in Winter! — it is best to keep yourself and the creative team in the safe playground of the actual physical and financial limitations from day one.”

What is the one thing you want people to know about you as a designer?

“If I can rephrase that to ‘remember about you’ it is this. That the most important thing is to look after your physical and mental health and that of your team, there will be other jobs so don’t break yourself on the current one no matter the pressure you may be under.

“I have been most fortunate to have my business partner and wife of forty years by my side at all of our major events and, alongside being an accomplished photographer, she has been responsible for the welfare of our teams on site and off. I would like all our crews, programmers, associates, trainees, creative peers and clients to remember their experiences with us as first and foremost damn good fun as we create together these little moments of history.”